Adult strabismus: causes, symptoms and treatment

25/11/2025

08/04/2019

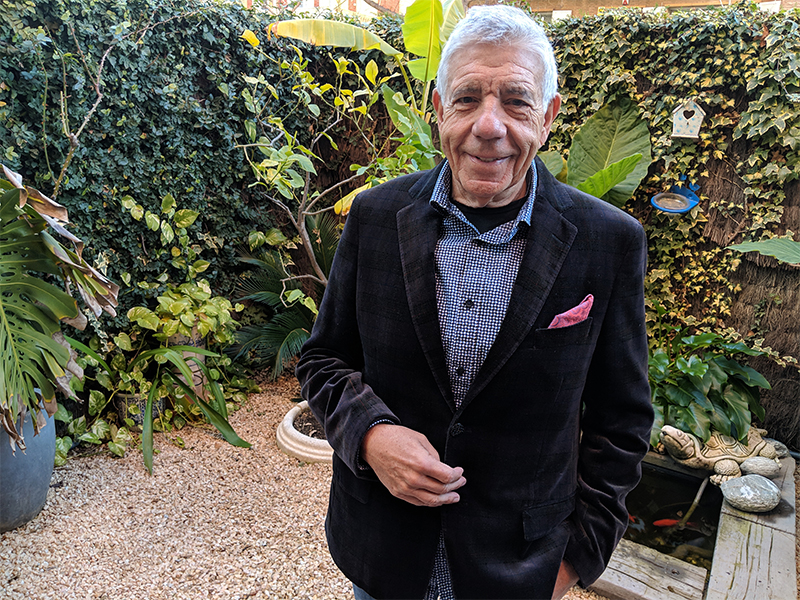

Born in Barcelona in 1948, Dr. Eduard Estivill is a doctor who is well known as a sleep expert. Author of numerous publications, he also has an artistic side which his band Falsterbo brings out in him.

You were very young when you received a scholarship to go study in the United States, where you came across the hippy movement and folk music. Was it this time spent abroad that cultivated your musical side with Falsterbo? How do you remember that period?

In the year 1966, my parents believed that it was important for me to learn English. I couldn't speak a single word (in fact, we only studied French at school), and my parents didn’t have the money for it. So, the only way that I could learn English was to get a scholarship somewhere. And after making efforts to get that scholarship, they sent me to a small town on the coast of California. I was there almost two years taking high school classes and the first few years of college... And that’s where I learnt everything I know about this type of music as a hobby. I completely immersed myself in American life, and obviously I learnt English, which has been so useful to me throughout my professional life. Logically, when I came back to Spain in ‘67 almost no other young people of my age could speak English like I could. There were very few and this opened many doors for me. First, as one of my hobbies: music - I translated songs with other friends and we’re still singing them nowadays. English was also a big help during my degree: I was able to do presentations in anglophone countries and it really has given me so many opportunities.

Why did you decide to study Medicine? Did your family influence your decision in any way?

Not at all. It was basically because when I came back from the United States, I was in contact with a group of Boy Scouts who were helping at a school for children with cerebral palsy. I experienced that part of my life with all the hopeful anticipation of an 18 or 19 year old, and I thought I could study medicine, more specifically, neuropaediatrics, having seen the needs of these individuals... And that’s how I made my decision. I studied medicine and then I undertook this specialism. To specialise in neuropaediatrics, first I had to do paediatrics at the Vall d’Hebron hospital, and then neurophysiology, a subject where we mainly carried out electroencephalographies on children. This links to why I later got into sleep medicine. At the hospital, I did tests on children, new-borns and very small kids... If we wanted the tests to work out properly, the children had to sit still—you can't do this test if the child is moving, just like you can’t do an electrocardiography if the person is moving. So, what we did (because the nurses taught me to do it) was sing all types of songs to them and wait until the children fell asleep, as we couldn’t give them any medication to make them go over. That’s where my interest in sleep came from. I leant about the sleep patterns of new-borns, I published work and I was able to go to Paris to study sleep patterns of new-borns with top specialists. The paediatrics and neurophysiology specialism at the Vall d’Hebron hospital lasted 8 years. After that, I got a position as assistant doctor in the Sant Joan de Déu hospital. I started in the neuropaediatrics service, basically overseeing the epilepsy, sleep and electroencephalography section. Then I got the chance to travel to the United States again, to a very important hospital in terms of the topic of sleep: the Henry Ford Hospital. So, at that time I decided to leave the hospital and pursue sleep medicine. When I came back I started up the department and I was lucky to be a pioneer in the field. At that time, not one single private unit existed, so we were the first to embark on this kind of work which turned out to be very rewarding, especially for those of us who worked on it, because it’s a specialist area where we can really help people.

Describe your day-to-day routine. What do you like most about your profession?

I’m so enthusiastic about what I do. In sleep medicine we can treat a wide range of problems. However, I also combine it with my hobbies. I really like sport and every day I try to go to my sport’s club: Barcino. I either play tennis or go to the gym. I also play golf from time to time, take part in a class the odd day of the week, and I balance it with guitar, music and songs. Which means I do plenty! Right now —now that I’m 70—I spread my activities out a little. On Monday and Tuesday, I do doctor's visits and on the rest of the days I combine all my activities with other professional work including writing articles, doing interviews, conducting scientific studies etc. We also have a foundation—the Estivill Sleep Foundation—, and we are doing really interesting things with regard to sleep and athletes. All these activities fill up my time and make me really happy too.

Is there any relation between sleep disorders and eye conditions?

Nowadays we know that there are many disorders related to sleep. And a long time ago we learnt that, for example, cardiac problems have to do with poor breathing at night (apnoea). However, we recently undertook a very interesting piece of work with Dr. Javier Elizalde. Some years ago, we were indeed given a prize for what is called floppy eyelid syndrome, a condition we see in the eyelids of individuals who, when they snore, suffer apnoea. This means there is friction between this eyelid and the snoring movement, leading to this condition. Along with Dr. Canut, we have made contributions related to glaucoma and sleep conditions. It has been proven that in people with apnoea, as they lack oxygen—because one of the consequences of apnoea is not enough oxygen enters our brain—, some of the brain's structures, like the eye, may suffer hypoxia, a lack of oxygen to the eye, which may cause, or have to do with glaucoma. And this is a topic that still needs to be studied. We have some research pending which may be of interest in the near future.

You worked with the Barraquer Foundation on an expedition to Africa. What was the highlight of your experience?

It was truly rewarding. One of the doctors, Gorka Martínez Grau, invited me to take part in the expedition as a paediatrician. We went to Malawi to work. They had already got into the routine of carrying out check-ups on people, and above all, visiting children with eye problems in order to diagnose them, then doing checks to determine if they had any retina conditions, myopia, astigmatisms or long-sightedness. These situations make you very grounded. You begin to think that you are in a world where everything is very simple: people eat, move around and love each other. Over there, sure, they love each other, but they eat little and move poorly. Fifty per cent of children die before the age of 5. It's dreadful. Plus, many contract malaria or AIDS, which means the impact is greater. When you go home you value what you have a lot more; but it creates a trauma in your mind. I had a really tough time when I got back, because I thought: what in the world are you doing visiting people who want for nothing while there are children dying of hunger in those countries? Coming back is hard, because you get so involved when you are there—at least I did—that this feeling of knowing you are so privileged and you don't appreciate it, makes you reflect on life a lot more.