Learn about refractive errors: myopia, hypermetropia, astigmatism and presbyopia

16/01/2026

23/04/2020

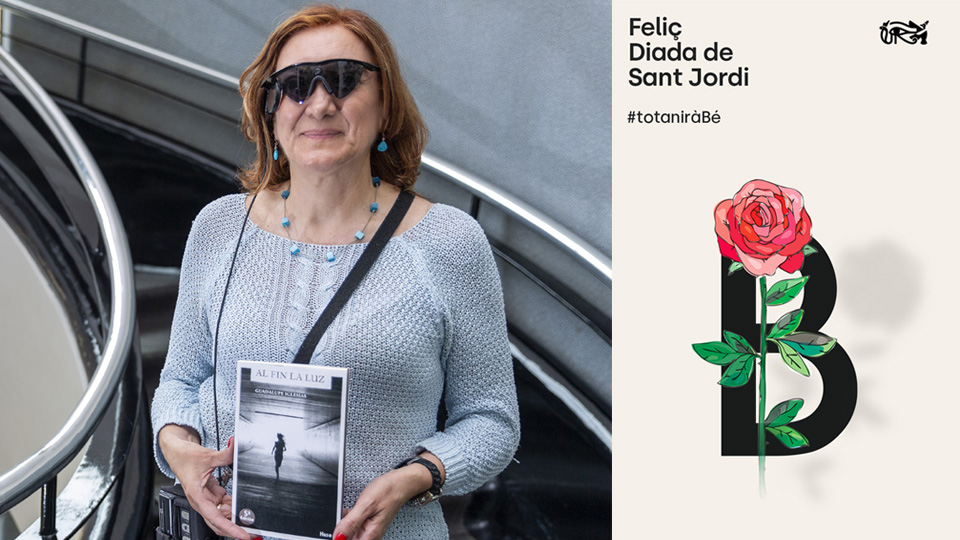

At the age of 30, she was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa and ten years later she had gone blind. Back then, Guadalupe never imagined she’d end up being part of a pioneering project in Spain that would restore her eyesight—the Argus II artificial vision device installed at the Barraquer Centre—and, even less that she'd share her adventure in Al fin la luz, her first book.

Retinitis pigmentosa entered Guadalupe’s life out of the blue. This genetic condition gradually deteriorates the photoreceptors, the eye cells sensitive to light, causing a loss of vision. In her case, at the age of 40 she was completely blind. A tireless fighter, she confronted the illness head on with hope and quickly became active and joined Retina Madrid, an association for people affected by generative retina conditions. She ended up becoming its vice-president.

One afternoon, Guadalupe attended a conference at the Spanish Foundation for Blind People (ONCE). There, Dr. Jeroni Nadal, retina and vitreous department coordinator at the Barraquer Ophthalmology Centre, was talking about his participation in a pioneering artificial vision project: the Argus II retina implant. “At first, I didn’t think that it would work for me”, recalls Guadalupe. But as the doctor continued talking in more detail about the type of patient who could benefit from the device for the restoration of their eyesight, she started to change her mind. She still remembers his answer when she raised her hand to ask if she could participate. “Don't think twice. Come to the clinic and have the tests done to see if you're a good fit. But let me tell you, some ships only sail once in life”, Dr Nadal responded.

“You can be happy with a disability".

Soon after, in December 2015, Guadalupe became one of the four lucky people to receive a bionic eye to restore part of their vision. After the operation, having checked that the sixty electrode implant in one of her eyes had not been rejected, she had her “lights on moment”, as she calls it. That’s when the device was enabled and she started to receive visual stimuli. “The only thing I perceived was white light, but I couldn't see anything. Little by little, with the help of rehabilitation team at the Barraquer Centre, they taught me to interpret that light so I could distinguish the shape and volume of objects”. This adventure culminated in Al fin de la luz, the book in which Guadalupe Iglesias recounts her intense learning process to see through the light.

Now Guadalupe is able to go out on her own, avoid obstacles and moving vehicles and distinguish people by their shape... Not only has she gained in independence and quality of life, she has even dared to do things that were unthinkable before: “I always used to panic in the underground, even when I could see, because I was scared of getting shoved and needed to hold onto someone else’s arm. But now I've learnt to get on the underground by myself. I can distinguish the windows of the carriage on approach and see the door perfectly when it opens", she explains, excited. She continues to go to her dance classes and has knitted a doormat for her home with her initials and her husband’s on it. When we ask what is the most important thing life has taught her, Guadalupe has a clear answer: “You can be happy with a disability".